India’s seed systems are among the oldest and most diverse in the world. Long before the state formalised agricultural regulations or private companies entered the sector, farmers, tribal communities, and women seed keepers nurtured, exchanged, and evolved seeds through relationships of trust, commons governance, and deep ecological knowledge. It is this decentralised, biodiversity-rich, community-led seed culture that has ensured India’s food resilience for centuries.

The Seeds Bill 2025, now under consideration, is being promoted by the government as a long-awaited instrument for improving seed quality, reducing spurious seed sales, and protecting farmers. But beneath this reassuring language lies a regulatory architecture that risks fundamentally altering the character of India’s seed economy. The Bill’s provisions, while technical on paper, have sweeping implications for farmers’ rights, indigenous knowledge, biodiversity, and future climate resilience.

On the surface, the Bill appears farmer-friendly. It reaffirms in Section 1 that “nothing in this Act shall restrict the right of the farmer to grow, save, use, exchange, share, or sell his farm-saved seed,” provided it is not sold under a brand name. This statement echoes protections in India’s landmark Protection of Plant Varieties and Farmers’ Rights (PPV&FR) Act, celebrated worldwide as the strongest farmers’ rights law.

However, the protection is narrower than it appears. The Bill defines “farmer” in a way that explicitly excludes farmer producer organisations (FPOs), cooperatives, community seed banks, tribal seed collectives, and any entity engaged in the commercial sale of seed. This means that the exemption applies only to individual farmers acting alone, not to the very institutions that sustain seed diversity in real-world India. Many of the most important indigenous and agroecological seed networks, especially women’s groups and tribal communities operate collectively. Under the new framework, these groups would be treated as seed “dealers” or “producers,” subject to registration, licensing, inspections, and penalties.

This poses serious risks. India’s seed culture is fundamentally collective. The revival of millets in tribal belts, the preservation of folk rice in eastern India, and the maintenance of drought-resilient landraces in arid regions all depend on groups and not individuals. Seed saving and exchange are social practices, often embedded in rituals, food cultures, and community institutions. Reducing the definition of “farmer” to an individual household ignores this communal reality and exposes community-led seed systems to regulatory burdens they are unable to bear.

A second area of concern is the Bill’s insistence that no seed, except farmers’ varieties and export-exclusive varieties may be sold without registration. Registration is tied to Value for Cultivation and Use (VCU) trials, which assess uniformity and stability. These trial criteria align well with corporate hybrid seeds, which are designed for homogeneity. But they are fundamentally incompatible with most indigenous and farmer-bred varieties that are intentionally varied, evolutionarily adaptive, and genetically diverse. In the context of climate change, such diversity is an asset, but under this Bill, it becomes a liability.

The Bill also mandates the use of a Centralised Seed Traceability Portal. Every actor from producer to distributor, must upload batch-wise data, generate QR codes, and maintain digital records. While this may improve transparency for large companies, it introduces a significant digital and administrative burden on small-scale seed actors. Community seed banks, tribal groups, and women-led collectives may struggle to comply with QR-based systems, making them vulnerable to penalties or exclusion. Seed exchange, historically governed by trust, could now be monitored and policed through a centralised digital infrastructure.

Moreover, the Bill grants Seed Inspectors expansive powers: the authority to enter premises, search, seize seed stock, freeze business operations for 15 days, examine documents, and issue penalties reaching up to ₹30 lakh or even prison time. Although due-process references exist, the scope for harassment especially in informal seed markets, haats, and tribal regions is significant. The threat of regulatory overreach could chill farmer-to-farmer exchange and seed commons, even if legally permitted.

Another critical issue is the Bill’s approach to seed imports. Imported seeds may be registered based on trials conducted in the exporting country without mandatory local agro-climatic testing. More troublingly, the Bill does not clearly integrate India’s biosafety regulatory framework (such as GEAC) into the import approval clause. This creates a pathway through which genetically modified or patented seeds could enter Indian markets under reduced scrutiny, potentially threatening both biodiversity and farmer sovereignty.

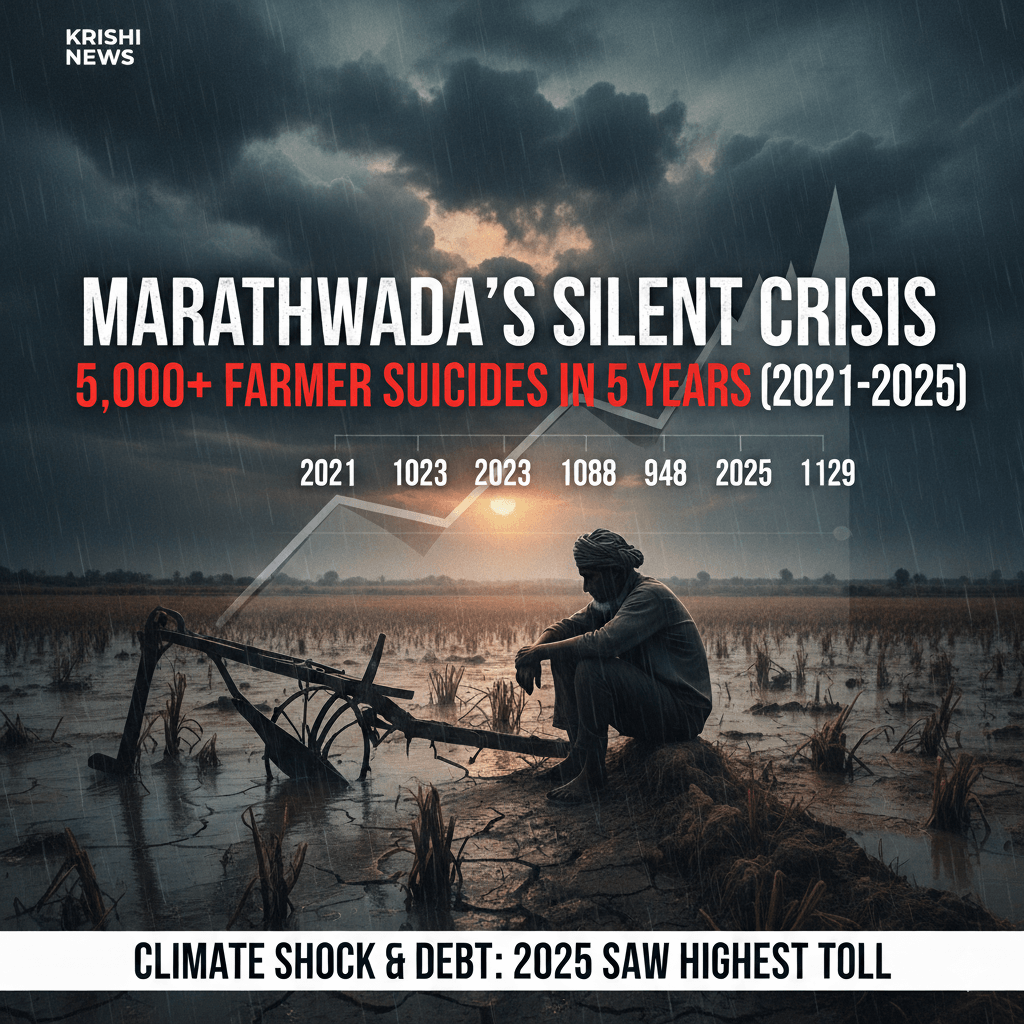

Farmers also face a “compensation vacuum.” Though the Bill demands that companies disclose “expected performance,” it does not establish a strict liability mechanism that holds seed companies accountable for crop failure due to poor-quality seed. This lack of timely compensation has long burdened Indian farmers, especially in cotton and vegetables, where failed hybrid seeds have triggered indebtedness and distress.

To be clear, India does need stronger seed regulation. Farmers deserve protection from fraud, substandard seeds, and exploitative pricing. But the Seeds Bill, as drafted, conflates quality regulation with centralisation and compliance-heavy governance. It risks creating a highly formalised seed market dominated by large firms, while marginalising the very systems that have preserved India’s agricultural diversity and climate resilience.

What is needed is simple and achievable:

- Extend the farmer exemption to include FPOs, cooperatives, SHGs, gram sabhas, and community seed banks.

- Clarify that transparency labels do not constitute “brand names.”

- Introduce time-bound compensation for seed failure.

- Require Indian agro-climatic VCU trials for all imports.

- Reduce inspector overreach through clear procedural safeguards.

- Protect customary seed exchange, indigenous knowledge, and commons governance.

India’s food future depends not on uniformity, but on diversity; not on surveillance, but on trust; not on corporate pipelines, but on community resilience. The Seeds Bill 2025 can either strengthen these foundations or weaken them irreversibly. The choice rests with the Parliament.