A twin agriculture crisis has erupted in the region: in Motha village, around 30 farmers who sowed the popular wheat variety LOK‑1 (cultivar “LOK-1”) report that their crop did not germinate at all, while in the neighbouring Paratwada-Dhamangaon region urea supply is in disarray, as dealers charge as much as ₹350, and farmers facing shortages and opaque invoicing.

Failure of the LOK-1 crop in Motha village

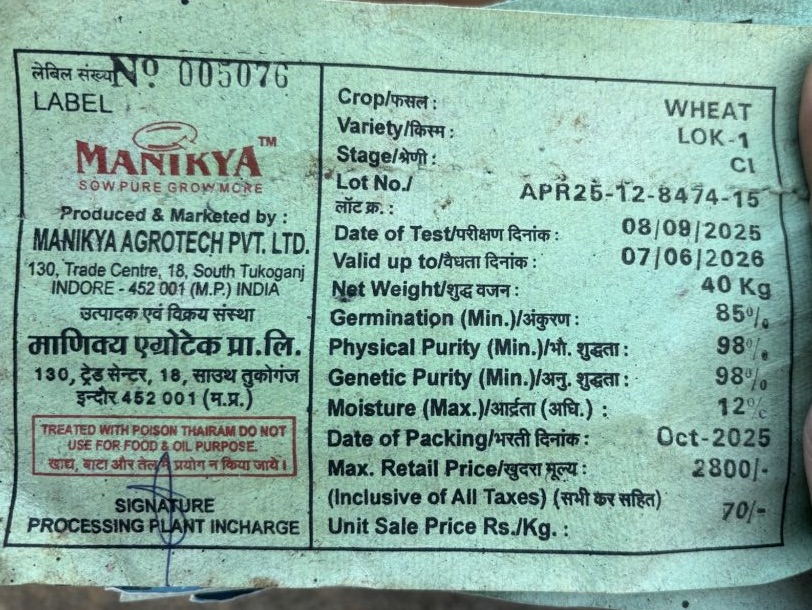

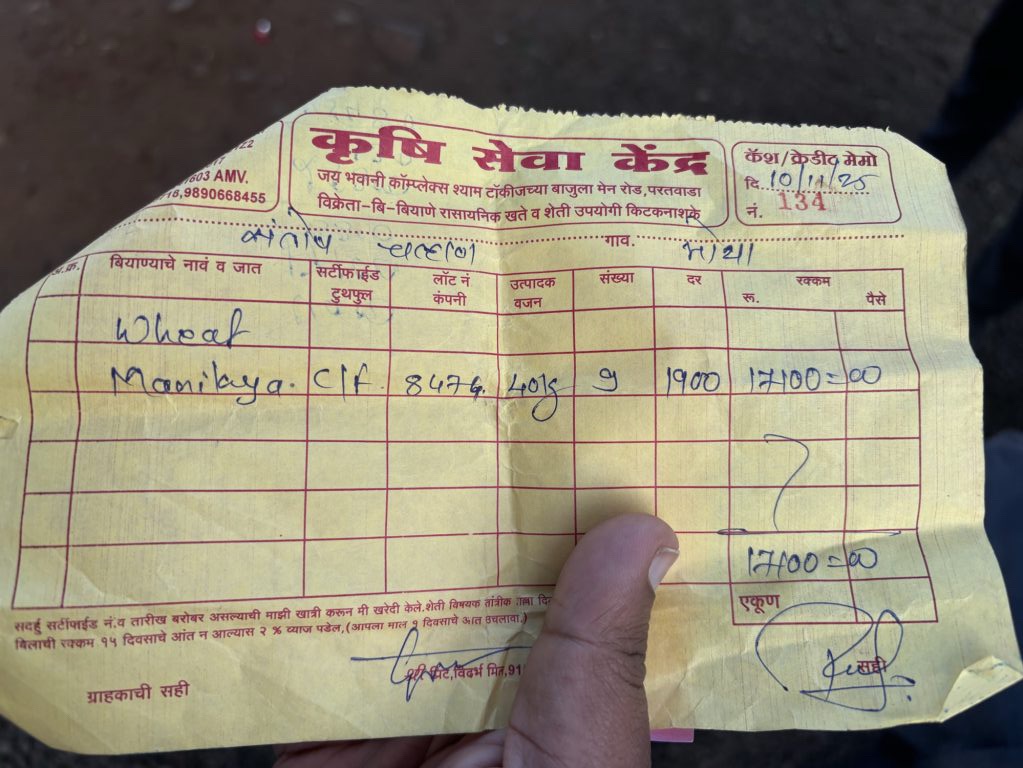

Farmers in Motha village are reeling after this year’s sowing of the LOK-1 wheat variety failed right at the germination stage. The variety LOK-1 has been widely adopted in central India for its early maturity and rust resistance (for instance, it has been a leading variety in Madhya Pradesh). In this case, roughly 30 farmers (with varying holdings) report that despite sowing the certified seeds in line with standard practices the crop simply did not sprout. The seeds were produced and supplied by Manikya Agrotek Private Limited, according to farmers and seed bags shown on site. The result: large areas lying bare, planting cost incurred, but no emergence. Local agitation is growing fast.

Responding to the uprising, officials from the Agriculture Department, Maharashtra visited the village today and registered formal complaints from the affected farmers. The visit signals recognition of the problem, but many farmers are demanding quick redress, either through seed replacement, compensation or re-sowing support.

Urea crisis in Paratwada-Dhamangaon region

Simultaneously, farmers in the Paratwada and Dhamangaon region of Vidarbha report acute shortage and price exploitation in the urea market. All “Krushi Kendra” are allegedly selling a bag at ₹350, for a bag which costs ₹266. When asked for bills or invoices, many dealers reportedly claim they have “no urea at all”.

These claims are consistent with broader national trends: India is facing a fertiliser supply challenge. According to recent analysis, opening stock of urea for 1 October 2025 was 3.7 million tonnes, nearly 2.6 million tonnes lower than a year earlier, raising fears of shortages for the upcoming Rabi season. Further, while the official MRP of a 45 kg bag of urea is fixed at ₹242 by the central government in practice farmers across states report paying several times that amount. Local farmers in this region claim that the disparity in prices and lack of bills point to unscrupulous trading, hoarding and diversion of subsidised fertiliser. The situation is exacerbating their distress because they cannot access urea at the subsidised rate, yet they need it to push wheat and other rabi crops after the failed germination.

Why this matters

- The failure of LOK-1 wheat germination means not only loss of yield, but also the loss of input costs (seeds, labour, land preparation). For small and marginal farmers, that can push finances to the brink.

- The urea shortage and inflated pricing undermine input-accessibility, particularly for lower-income farmers who rely on subsidised fertiliser for cost-effective production.

- Both issues combine to erode trust in the system: in seed quality, in input supply chains, and in local dealer networks and departmental oversight.

What farmers are asking for

- In Motha village: immediate seed-audit of the batch of LOK-1 distributed (to check germination rate, quality, certification), replacement of defective seed, and compensation or resowing support.

- In Paratwada-Dhamangaon: urgent rationing of subsidised urea bags to genuine farmers, transparent billing/invoicing, crackdown on dealers charging above MRP, and reliable supply assurances for the rabi season.

- In both cases: departmental accountability and a local grievance cell so farmers can register complaints and get timely redress.

What officials say / need to do

The Agriculture Department’s visit to Motha is a positive step; however, a thorough investigation is required on seed source and handling. On the fertiliser front, there must be stock-verification, dealer-audit, and enforcement of the MRP regime. Given national data showing a supply–demand gap in urea for 2025, local upward price deviations and shortages are not isolated incidents.

Looking ahead

If the issues remain unaddressed, the upcoming rabi season in the region could suffer reduced sowing area, delayed planting, or higher cost of cultivation. That in turn will hurt yields, incomes, and the broader food-system resilience in the region. The convergence of seed failure and input crisis underlines the need for strengthening local supply-chains for both quality seed and subsidised fertiliser, particularly in marginalised agrarian areas like Vidarbha.

For the portal readers and region’s farming community:

Farmers in the affected zones should document the seed bags, germination failure (with photographs if possible), and keep purchase/invoice receipts for fertiliser. They should submit these together with signed anecdotal affidavits to their local agriculture-officer. Meanwhile, department officials should publish a list of authorised urea-dealers with current stocks, and hold public verification meetings in taluka-level offices to restore confidence.