A food systems analysis of the Nagpur protest.

November 7, 2025

When farmers led by Prahar Janshakti Party chief Bacchu Kadu blocked National Highway 44 in Nagpur for three days in late October, it wasn’t just another agrarian protest—it was a symptom of systemic failure decades in the making. The agitation, which brought traffic to a standstill in Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis’s hometown, ended with a familiar political compromise: a six-month committee to study loan waivers, with a decision promised by June 2026.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth that food systems research compels us to confront: the demands raised are, complete farm loan waivers, guaranteed Minimum Support Price (MSP) for all crops, NAFED procurement for soybeans, and immediate crop loss compensation, are recycled solutions to a structural crisis that requires transformative intervention, not temporary relief.

The Numbers Behind the Crisis

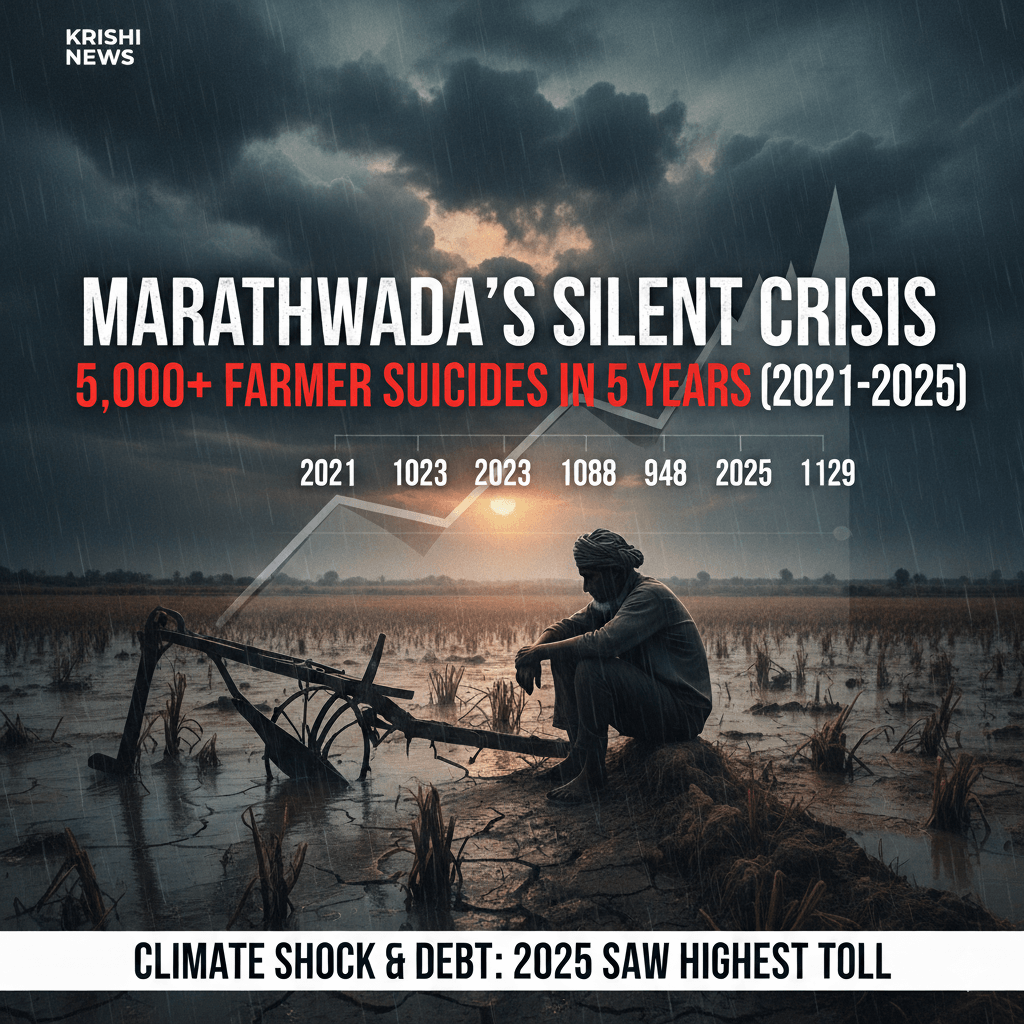

The urgency is undeniable. Between January and March 2025 alone, 767 farmers took their own lives in Maharashtra, an average of eight suicides per day. By April, that number had risen to 869, with Vidarbha’s Amravati division recording 327 deaths and Marathwada reporting 269. In Marathwada’s Beed district, 71 farmers died by suicide in just three months, a 32% increase from the same period in 2024.

The state government has responded with what it calls the largest relief package in Maharashtra’s history: ₹31,628 crore for crop losses due to unseasonal rains that devastated 68 lakh hectares across 29 districts. Of this, ₹8,000 crore has been distributed to 40 lakh farmers. Yet protests continue, debt persists, and suicides mount.

Why do interventions fail to stem the crisis?

The Evidence Against Loan Waivers

Research from the Institute for Studies in Industrial Development reveals that loan waivers “work as a temporary palliative to the debt stress faced by farmers but will not have a long-term impact on improving their living conditions”. The empirical evidence is damning: waivers disproportionately benefit better-off farmers, lead to lower future investments and productivity, and result in selective credit rationing by banks.

Even Chief Minister Fadnavis acknowledged this week that “loan waivers did not benefit farmers directly, they benefited banks”. His government has subsequently formed a high-powered committee under former chief secretary Praveen Pardeshi specifically to find “strategies beyond periodic loan waivers,” tacitly admitting their ineffectiveness.

Data from nine state loan waiver schemes implemented since 2014 shows that only 50% of beneficiaries actually received write-offs. Post-waiver periods consistently see banks tightening credit access, making it harder for farmers to secure loans for subsequent crop cycles-creating the very debt trap waivers ostensibly aim to break.

A 2022 State Bank of India study revealed agricultural non-performing assets (NPAs) rose from 2% before the 2008 waiver to 6% by 2017, demonstrating how waivers undermine credit discipline while fostering expectations of future bailouts. As one SBI economist warned, loan waivers have “delirious consequences on bank NPAs, agri-credit growth, and public investment in agriculture,” emphasizing the need to create markets rather than repeat this “vicious cycle year after year”.

The MSP Illusion

The demand for guaranteed MSP for all crops reflects farmers’ desperation for income security, but the mechanism itself is fundamentally flawed. The 2015 Shanta Kumar Committee report revealed that only 6% of farmers actually benefit from the current MSP system, meaning 94% receive no advantage whatsoever.

Research published by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) confirms that MSP functions more as a procurement mechanism for the National Food Security Act than genuine farmer support. The system primarily benefits wheat and paddy producers in Punjab, Haryana, and western Uttar Pradesh, while marginalizing farmers cultivating other crops.

More insidiously, MSP-driven procurement has distorted crop patterns across India, including Maharashtra. Excessive focus on rice and wheat has discouraged cultivation of pulses, oilseeds, millets, and horticulture products with higher market demand and nutritional value. This monoculture trap depletes soil health, exhausts groundwater, and locks farmers into low-value commodity production.

Analysis from the International Institute for Sustainable Development shows that from 2000-2016, Indian farmers actually received less than international prices, meaning current policies effectively tax farmers rather than support them. MSP benefits 13% of rice farmers and 16% of wheat farmers, while input subsidies disproportionately benefit large farmers and fertilizer companies, not the small and marginal farmers who constitute 86% of India’s agricultural workforce.

The Food Systems Failure

What the Nagpur protest reveals is not just an agricultural crisis but a food systems failure. Food systems thinking demands we examine not merely production but the entire web of relationships connecting agriculture, nutrition, environment, and livelihoods.

Consider the paradox: India produces 354 million tonnes of food grains annually, a surplus by any measure. Maharashtra itself is a food surplus state. Yet rural households remain malnourished, children under five face severe nutritional deficiencies, and farmers earning this surplus are suicidal. The reason lies in what food systems scholars call “single-metric optimization.” For 50 years since the Green Revolution, India’s agricultural policy has optimized for maximum grain production—calories, not nutrition; procurement, not markets; chemical inputs, not soil health; government buying, not farmer prosperity. Research from ICRISAT identifies a “triple bind” that incremental reforms cannot resolve: an economic crisis where average non-farm income is twice that of farming; a nutritional crisis where food surplus coexists with widespread deficiencies; and an environmental crisis where one-third of agricultural land is degraded, half the districts face water stress, and soil organic carbon is critically low.

The Nagpur protest demands address none of these underlying drivers.

The Political Economy Challenge

Why do politicians repeatedly choose waivers despite overwhelming evidence of their ineffectiveness? Research suggests the rationale “does not lie so much in the economic benefits that it delivers to distressed farmers but it is more likely a product of the peculiarities of the policy-making process in India”. Loan waivers are “ostensible political decisions taken by political actors with a view to appropriate concrete political gains”. They provide immediate electoral relief at relatively low political cost, while structural reforms require sustained investment, political capital, and time horizons extending beyond election cycles.

Maharashtra’s fiscal position compounds the challenge. The state government projects debt of ₹9.32 lakh crore for FY 2025-26—the highest in the state’s history. The Ladki Bahin Yojana allocates ₹36,000 crore annually for cash transfers to women, while the crop loss relief package consumes ₹31,628 crore. These commitments leave limited fiscal space for infrastructure investment. Yet this is precisely why Maharashtra cannot afford another waiver. The ₹32,000 crore being spent on reactive relief, if invested in permanent infrastructure, soil health, processing facilities, market linkages, and climate resilience it would transform farming for a generation rather than provide temporary respite for one season.

The Path Forward

Bacchu Kadu called off the Nagpur protest declaring “this is only the end of the first phase the movement will continue”. He’s right that the struggle continues, but the question is: struggle for what? If farmers demand more of the same failed interventions—waivers that don’t waive debt, MSP that doesn’t reach them, procurement that doesn’t pay fairly—they condemn the next generation to the same cycle. Maharashtra’s eight daily farmer suicides are evidence that the current approach has catastrophically failed.

Food systems transformation isn’t utopian, it’s practical and evidence-based. Organizations like ICRISAT, IPES-Food, and regional research institutions have demonstrated what works: diversified farming systems, regenerative agriculture, farmer-controlled value chains, direct income support, and climate-resilient infrastructure. The Maharashtra government itself admits waivers haven’t worked by forming a committee to find alternatives. The challenge now is ensuring this committee doesn’t produce another politically expedient band-aid but genuinely transformative policy.

Farmer leaders, agricultural scientists, civil society organizations, and policymakers must demand redesign, not relief; systems change, not subsidies; sovereignty, not survival. The ₹32,000 crore relief package represents a fork in the road: invest it in temporary palliatives that perpetuate the crisis, or channel it toward permanent solutions that make Maharashtra a model for food systems transformation in India.

The choice will determine whether we’re writing this same analysis about another protest three years from now or celebrating the beginning of genuine agricultural renaissance.